Every year, thousands of people enjoy the crystal-clear water of Blue Grotto and other north-central Florida springs. Water this clear is a rarity throughout most of the United States. So where does this incredible water come from?

Where it doesn’t come from

Had you asked someone 40 years ago where north-central Florida’s spring water originates, you would be told it comes from the mountains of northwest Georgia and southeast Tennessee. Supposedly, this water would travel hundreds of miles underground before finally surfacing in our local springs and sinkholes.

It’s unclear where and how this theory originated. But it’s completely false.

The real source of Florida’s spring water

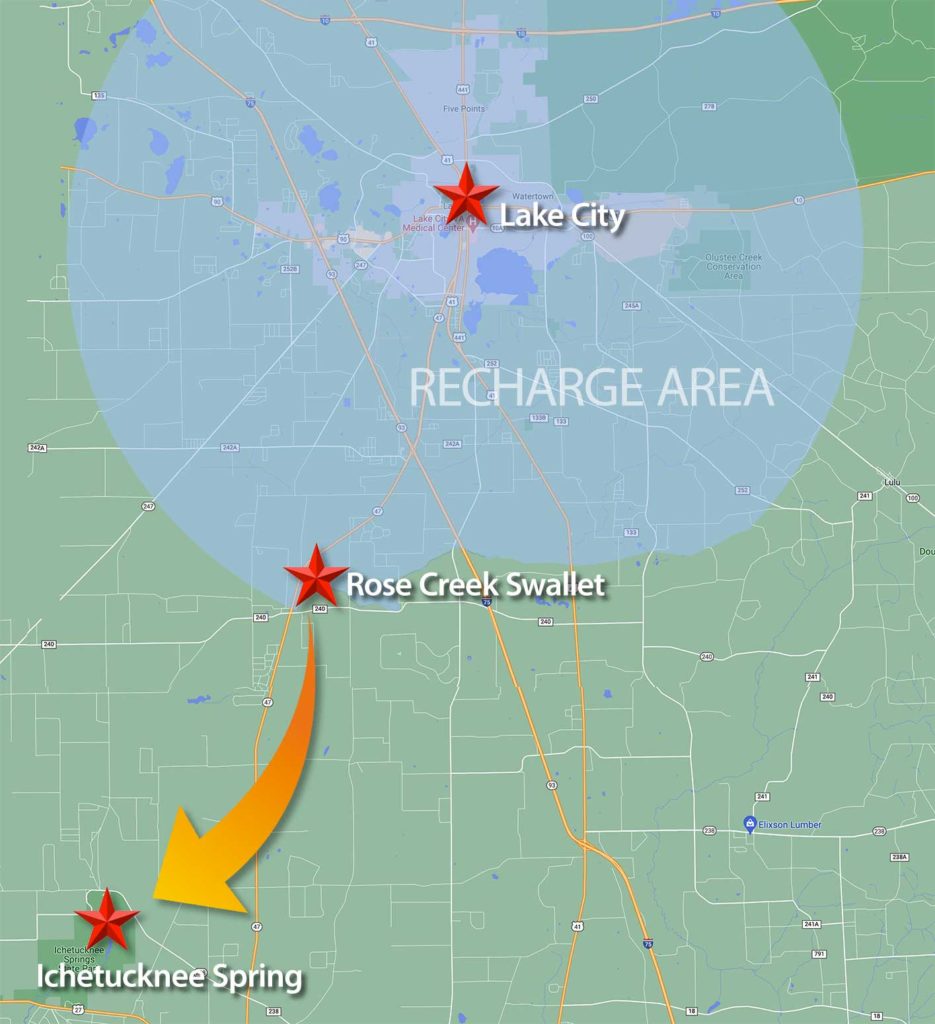

The real source of our water is rain falling within the immediate vicinity of the spring. These recharge areas will vary in size but can be as small as twelve miles in diameter.

We determine the size of a recharge area through a process known as dye tracing. Researchers release a special dye at a place where rainwater is going underground. If the dye later appears in a nearby spring or sinkhole, we know the release point is part of the recharge area.

The dye is visible when released but quickly dissipates as it moves downstream. This makes it difficult or impossible to detect visually. To confirm the presence of dye, divers rely on dye traps. A typical dye trap is a packet of activated charcoal sealed inside a permeable membrane.

As water passes through the trap, it absorbs traces of the dye. The trap is then taken to a lab where the presence of dye is confirmed. This establishes that the collection point is, in fact, downstream from the dye-release point.

Dye tracing in action

In 1987, A&E Network helped sponsor a project to determine the source of the water coming out of Ichetucknee Spring. It was theorized that the source of the water was something called Rose Creek Swallet, south of Lake City.

The region south of Lake City is a natural basin. Rain that falls here eventually drains into Rose Creek. The water then travels several miles to the swallet near the Columbia City crossroads. Here it disappears into an underwater cave.

If you look at the map, you can see why researchers assumed that Rose Creek Swallet was the source of the water coming out of Ichetucknee Spring. Proving it, however, was not easy.

The Project

A project of this scope involved over two dozen individuals, most of them volunteers and cave divers. Among them was one of our Blue Grotto staff members. We needed this many people because of the number of collection points that had to be monitored — and because the entire project was being filmed for a special on A&E.

- The A&E side of the project was being headed up by producer Bill Kurtis.

- The diving side was organized by well-known cave explorer and cinematographer Wes Skiles.

- We began by placing dye traps at more than a half-dozen collection points. Most of these were inside small underwater caves that surrounded Ichetucknee Spring.

- Once the traps were in place, a team led by Dive Rite president Lamar Hires went over 1,000 feet back into the cave at Rose Creek Swallet and released the dye.

All that remained at this point was to see when and at which collection point the dye appeared.

The collection process

Our role in the project involved making a daily two-mile hike back into a mosquito-infested, jungle-like forest. The August heat and humidity didn’t help.

- At this point we came to a 20-foot-long fracture in the forest floor, just wide enough for a person to squeeze through at its widest point.

- The fracture dropped a dozen feet to the water. At this point, it began to widen.

- Our job was to hit the water and drop down 90 feet to a medium-size cave room. At the back of the room was an opening that looked into the side of a small cave passageway that we assumed went to Ichetucknee. This is where the dye trap was.

- Every day we would collect the dye trap and replace it with a new one. The old dye trap would then go to the lab.

The entire process took about two hours. This involved hiking in, setting up, making the dive and then hiking out again. The dive itself was around five minutes — most of this time spent making a slow ascent and safety stop.

The results

After a week, dye finally appeared at a collection point close to Ichetucknee Spring. It never appeared at the site we were monitoring.

While this may sound like a bit of a bust, it wasn’t. What it helped establish is that, while most of the water coming out of Ichetucknee Spring comes from the Lake City recharge area, some of it likely comes from other areas.

Bill Kurtis and Wes Skiles turned all the footage we shot into a half-hour segment on A&E’s New Explorers series entitled Polluting the Fountain of Youth. If you can find this segment, you’ll see not only the dye release but our first expedition to the fracture in the woods.

And what about Blue Grotto?

To date, we’ve not established what the recharge area is for Blue Grotto and neighboring Devil’s Den. Doing so would be a very expensive and time-consuming process and there is not exactly a pressing need. Given the direction in which the water moves, we suspect the recharge area is to the immediate north of us…but we can’t know for sure.

Groundwater flow in the Williston area is exceptionally weak compared to other parts of north-central Florida. We suspect it was not always this way given that, at one time, there was enough water moving through the area to carve out both Blue Grotto and Devil’s Den.

Where the water goes after it leaves us is also a mystery. It appears to be headed in the general direction of Rainbow Spring, the headwater of Rainbow River. This does not mean it surfaces there. It could come up somewhere else entirely.

These mysteries are part of what makes our job so enjoyable. We hope you appreciate them as much as we do.