You can enjoy the natural beauty of Blue Grotto without knowing anything about what created it. But the more you do understand, the more fascinating things become.

In this article, we’ll share what we know — and what we assume — about this process. This way, the next time you visit you will be able to say, “So that is why this particular feature is here.”

Understanding karst topography

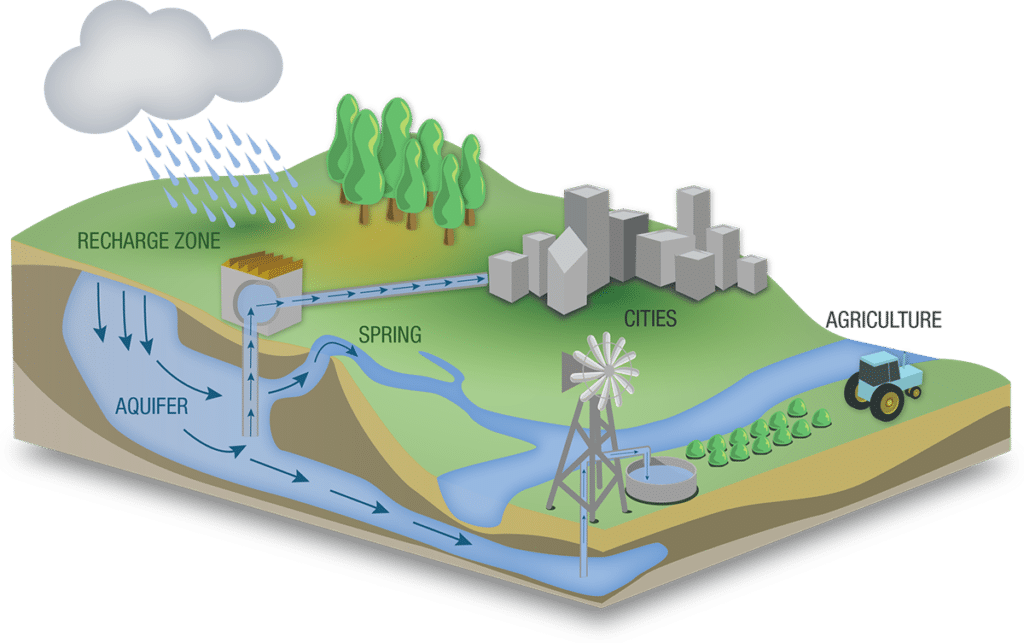

Karst is a term geologists use to describe topography that is conducive to the creation of caverns and caves. Beneath a thin layer of limestone, most of north-central Florida consists of what geologists have dubbed Ocala limestone. Like many other forms of limestone, this rock is extremely porous and can easily become saturated with water.

- The average elevation of the Williston area is 75 feet. The water table sits 15 to 25 feet below this meaning that it is still 50 feet or more above sea level. Thus, gravity is constantly pulling this water toward the ocean.

- While the water is capable of moving through the rock itself, it always seeks the path of least resistance. One such path is provided by bedding planes. These form at the boundaries between different layers of limestone.

- When the different layers of limestone expand and contract at different rates, the friction between the two can create a bedding plane. Bedding planes create a perfect conduit for water seeking to escape to the ocean.

- The next time you are in the Grotto, look at the ceiling near the back of the cavern. You will see a very distinct bedding plane.

Yet another avenue for escaping water is created by what we call spongework. As rainwater falls on north-center Florida, it absorbs carbon dioxide both from the atmosphere itself and especially from decaying organic matter on the ground. This forms an extremely week solution known as carbonic acid.

- Rain in north-central Florida is immediately absorbed underground. You will notice that, unlike the rest of the country, we have very few roadside ditches. We generally don’t need them to carry away rain runoff.

- Even though carbonic acid is weak, over time it can eat away at weaker pockets in the limestone. This creates a swiss-cheese-like formation known as spongework.

Given sufficient time (we’re talking millennia here), these pockets may connect with one another, forming conduits known as phreatic tubes. These provide an ideal avenue for water making its way to the sea.

There is an interesting phenomenon that can happen when the diameter of a phreatic tube exceeds nine centimeters. That is, the dissolution rate of the limestone accelerates. This can make one particular phreatic tube the dominant conduit for water traveling through a particular area. Most of north-central Florida’s extensive network of underground rivers and caves formed this way.

Springs vs. sinkholes

These are not the same thing.

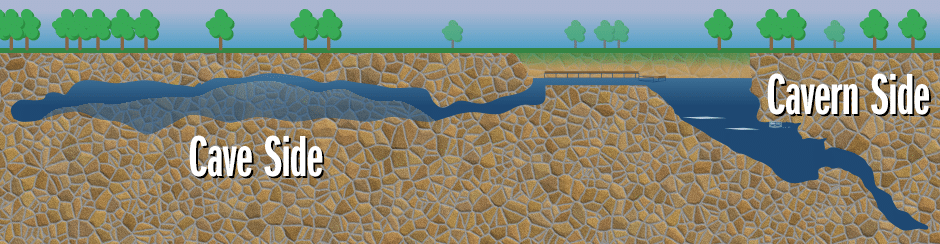

- A spring is a resurgence of water from underground. The water, once at the surface, remains at the surface. It then travels, via a spring run, to an adjacent river where it eventually reaches the ocean. Sites such as Ginnie, Manatee and Troy are springs.

- Sinkholes occur when unstable rock and soil collapse on top of or adjacent to an underground river. Any water that surfaces goes back underground. Blue Grotto, Devil’s Den and Paradise are all sinkholes.

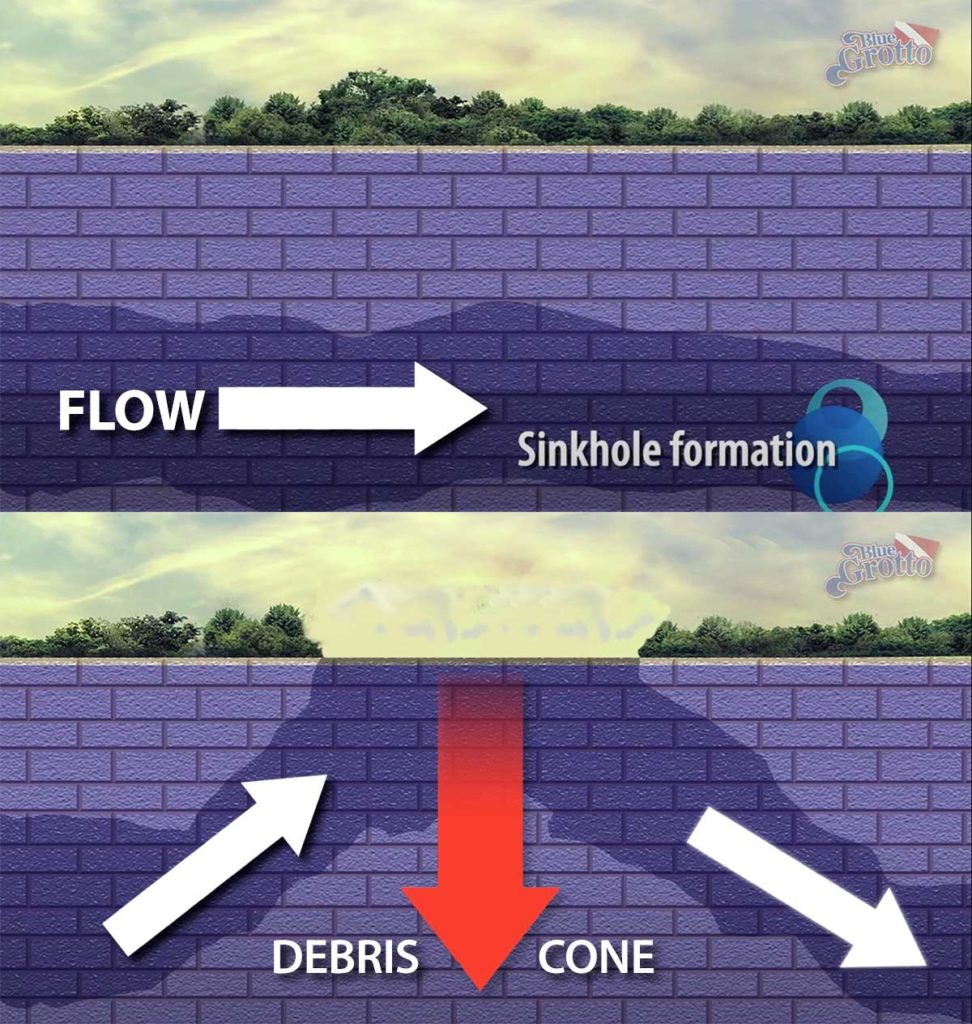

There are two general types of sinkholes.

- Inline sinkholes form directly over an underground river. They are usually circular in appearance and will have a spring side and a siphon side. The center of an inline sinkhole usually holds a debris cone, formed by rock falling in from the unstable ground above. Devil’s Den is a classic example of an inline sinkhold.

- Offset sinkholes form adjacent to an underground river. Instead of having a central debris cone, they will typically have a bottom that slopes toward the underground river. Blue Gotto and Catfish Hotel are offset sinkholes.

Mapping it out

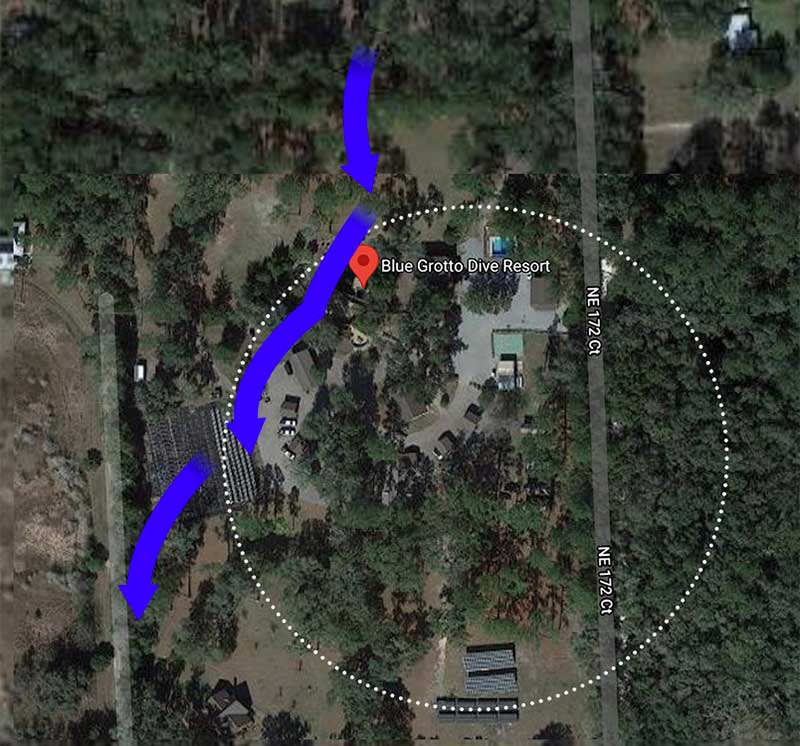

Evidence suggests that Blue Grotto Dive Resorts sits atop a roughly circular area of unstable rock and soil. If there was an underground river passing directly below this circle, we would likely have a massive inline sinkhole where Pavilion 2 now sits. What happened instead is that the underground river that formed the Grotto just grazes the northwest edge of this circle.

The evidence for this is the fact that, when you look at an aerial view of the Grotto, the cliff over the water forms part of an arc of a circle. Then, when you overlay a map of the cave that lies under the far end of the parking area, you see that his arc continues along the western edge of the cave.

What’s interesting about this arrangement is that only the spring side of the sinkhole has collapsed and is exposed to air. The siphon side remains completely underground.

Going with the flow

Compared with sites such as Ginnie and Manatee Springs, which output millions of gallons of water every day, groundwater flow through the Williston area is relatively week. This is unfortunate as a strong current is one of the things that helps keep springs crystal clear.

This being the case, we chose to help things along. If you look at the area behind the dock, you’ll see a square opening. This leads to a large-diameter tube running underneath the deck.

Walk to the back corner of the deck and you will hear the noise of a hydraulically driven impeller. This helps recreate the flow artificially, moving water from the spring side of the sinkhole to the siphon side. It’s one of several steps we take to help ensure our visitors enjoy the clearest water possible.

See for yourself

The next time you visit the Grotto, look for some of the things we discussed in this article. We can pretty much promise you that you will begin to see features you never noticed before.

That’s one of the great things about the Grotto. There is something new to discover on every dive.